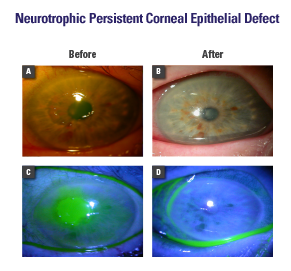

Neurotrophic Persistent Corneal Epithelial Defect

Ophthalmic Consultants of Chicago

Robert Mack, MD, is a magna cum laude graduate of Cornell University and graduated with distinction from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, where he served as president of the medical honor society. Dr. Mack is the recipient of both the Arthur J. Maschke Award for Excellence in the Art and Science of Medicine and the Irwin H. Lepow Award for Excellence in Research. He is a board-certified ophthalmologist and completed fellowship training in corneal and refractive surgery. Dr. Mack has served as an Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology at Rush Medical College and as co-investigator for several excimer laser clinical trials. He is also a member of the editorial board of the Journal of Refractive Surgery. He is not a consultant for Bio‑Tissue.

ROBERT MACK, MD – CHICAGO, IL

Overview

Neurotrophic persistent corneal epithelial defect (PED) is a degenerative corneal disease induced by an impairment of the trigeminal nerve. Impairment or loss of corneal sensory innervation is responsible for corneal epithelial defects, ulcer, and perforation.1 Neurotrophic PED is also characterized by decreased corneal sensation, epithelial breakdown, and poor healing. Coexisting ocular surface diseases such as dry eye, exposure keratitis, and limbal stem cell deficiency may worsen the prognosis. The disease progression is often asymptomatic and may lead to corneal infection and melting/perforation. Conventional treatments fail to promote prompt healing and tend to leave a corneal scar if healing does not occur immediately. Cryopreserved amniotic membrane contains nerve growth factor (NGF), which facilitates epithelial healing and helps recover corneal sensitivity2

Diagnosis

- History: Previous herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis, diabetes, surgery, or irradiation

- Symptoms: Blurry vision with minimal discomfort

- Examination: Central or paracentral epithelial defect (with fluorescein staining), infrequent blinking, decreased corneal sensation, and low tear meniscus

- Microbiological examination should be performed to exclude bacterial, fungal, or viral infections if there is inflammatory infiltrate

Treatment Strategy

- Restore corneal integrity by reducing inflammation, promoting healing, and preventing haze (PROKERA®) together with tapesorrhaphy3

- Treat underlying cause (eg, antiviral)

- Treat associated dry eye (punctal occlusion)

- Prevent further damage (withdraw unnecessary topical drugs)

- Reduce the risk of secondary infections (avoid bandage contact lens [BCL])4

Case Study

- A 67-year-old patient had a history of HSV keratitis and dry eye. She presented with mild ocular discomfort and progressive diminution of vision (20/400) over several weeks.

- Examination revealed a central corneal epithelial defect surrounded by a rim of loose epithelium, stromal edema, and anterior chamber inflammatory reaction (Fig. A, C)

- PROKERA® was placed along with punctal plug, tapesorrhaphy, and oral acyclovir

- Complete healing occurred within 1 week, resulting in clear cornea, 20/20 vision, and improved tear meniscus (Fig. B, D)

Conclusion

Early intervention with placement of PROKERA® promotes regenerative healing and prevents haze.